On Unintended Consequences

A computer lets you make more mistakes faster than any invention in human history - with the possible exceptions of handguns and tequila.

– Mitch Radcliffe

The art and science of developing software requires a constant stream of decision making. The more I work with software the more I begin to understand how each small decision can build up to a major consequence for program. Learning to think about the consequences of our design decisions early on helps us to anticipate possible problems before they can cause real damage.

Lend-to-Friend Demo

A few weeks ago I had the opportunity to demo a rapidly prototyped rails application that I made. The application, called “Lend-to-Friend”, is a peer-to-peer lending/borrowing marketplace intended for deployment in geographically proximate communities like college campuses, workplaces, or neighborhoods. During my demo I made an offhand remark about some of the application’s design choices such as keeping a user’s borrowing history hidden from other users in the interest of user privacy. An astute audience member asked why, if privacy were a concern, I would have chosen to protect a user’s borrowing history while still prominently displaying each user’s address on their Lend-to-Friend profile page.

The answer to this question was that the inclusion of user addresses in public pages was a result of my desire to make the site look a little more dynamic and interesting for a demo audience. In an ideal world, I explained, the disclosure of address information would have been far more nuanced–a generalized location displayed publicly and a complete location displayed privately to each party to a transaction only after they both affirmatively opted-in to the loan. Building out this system was both non-optimal use of limited resources and would have made demoing the application far more cumbersome. I explained essentially that the public display of user addresses was a calculated short-cut made in the interests of user-experience (for the demo) and developer resource allocation. In that circumstance I was lucky that I could give a reasoned answer about why I had chosen to do things the way that I had and explain a clear path to implementing a fully functional application that was ready to be put into production. While my demo audience agreed that I had probably made the best choice for this project, the stakes are much higher in the real world.

Client-Side Location Data

A few weeks later I found myself discussing a quick question about using client-side JavaScript to access the geolocation web API through the getCurrentPosition() method. Here is the prompt for our discussion:

[40.779437,-73.963244],[40.738527,-74.005363],[40.729975,-73.980926]

- The array of coordinates above are the locations of your friends, find the:

- Closest friend relative to your position

- Farthest friend relative to your position

Probably as a result of my recent (friendly) grilling on confidentiality of user location data, this prompt set off immediate alarm bells for me. The current location data of the individuals referenced in the prompt is provided within somewhere in the vicinity of 1/10th of a meter of accuracy! While a site could easily be built like this: i.e. serving precise lat/long coordinates via API and leaving processing up to the client-side, I had to question whether this was really a sound design choice? I have a lot of learning to do about the myriad factors that might impact this kind of decision in production but I took this prompt as an opportunity to at least begin wrestling with these difficult concepts.

If the goal is merely to report the identity of the individuals who are closest and furthest from your position, why would one need to dispense such accurate location data to the clients? This is awfully sensitive data that could be used to determine a good deal more about those individuals than their relative distance from a particular point.

After a bit of thinking it seems to me that nine times out ten designing an application in this manner is a risky proposition. It is naive to expect that merely because one’s interface is designed to display only a narrowly tailored piece of information such as “which individual is closest to me” that the data used to derive that information client-side will not be accessed and used to other unintended ends.

Admittedly there are some circumstances that I can imagine where this would a perfectly reasonable design choice with regards to privacy. One such example is an application where users explicitly opt-in to share their high-precision present locations with each other. Among small trusted groups, this kind of sharing is often a desirable and expected feature. Most of the time, however, location-enabled applications are aiming to achieve a far more generalized degree of location sharing and users would likely be quite disturbed to learn that such precise data was being disclosed without their knowledge.

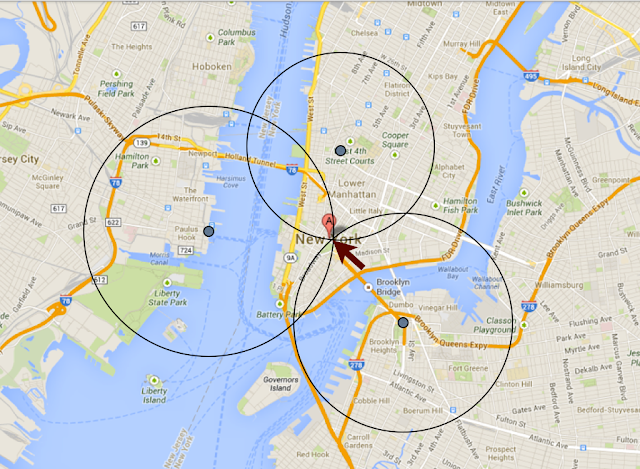

The popular location-based dating application Tinder publicly confronted this very issue in late 2013–2014. In order to conveniently facilitate romantic connections between singles, Tinder provided a potential match’s rough distance from the user. In the summer of 2013, reports surfaced that Tinder’s API had, for an unknown but relatively brief period, been disclosing highly sensitive date about potential matches including their most-recent location coordinates. Early the following year, security researches at IncludeSecurity publicly disclosed that although the Tinder API was no longer disclosing precise location coordinates for prospective matches, but that it was providing precise distance measurements. Combined with the basic high-school level trigonometry method of trilateration, this data could easily be used to determine the exact location of the individual (within about 100ft).

An example of how trilateration might be used to determine a individual user’s location

An example of how trilateration might be used to determine a individual user’s location

IncludeSecurity even created a proof of concept web-application that could return the location for any supplied Tinder user. Tinder has since fixed the issue but the breach of trust undoubtedly scared off some number of current or prospective Tinder users. Its important to note that Tinder got lucky in that it discovered what was going on from a well-intentioned security researcher that approached the company privately, alerted them to the vulnerability, and disclosed it to the public only after the issue had been mitigated. It doesn’t take too much imagination to see how much worse that story could have been for both Tinder and its Users.

My biggest takeaway from trying to grapple with this scenario is to understand the way that my decisions as a software engineer can have serious implications the reverberate well-beyond the immediate technical context in which I make them.

Looking Back With Fresh Eyes

After my dive into the question of how and where to responsibly deal with shared location data, I faced a hard truth: the chances were extremely high that if I went back to my Lend-to-Friend application, I was going to find a security vulnerability or a data leak that I was completely unaware of at the time I demoed it. I resolved to try my best to find a hole in my application that might be identified and potentially exploited by someone with more experience than myself.

I researched rails security issues and reviewed rails security checklists. I even tried running Brakeman, a highly recommended static analysis vulnerability scanner for Rails and scanning my deployed site with Qualsys SSL Labs scanner. Some of what I found was already on my radar and much of it needed to be bookmarked for future reading. Brakeman flagged a few lines of code it thought were problematic and it has been really helpful to try to understand what I could have done better/differently and what risks that code might realistically currently pose.

One issue jumped out at me as particularly interesting because it seemed so straightforward that the moment I saw it, I could not imagine how I could have failed to recognize it in the first place. Bruno Facca suggests in his Zen Rails Security Checklist that applications should:

[a]void exposing numerical/sequential record IDs in URLs, form HTML source and APIs. Consider using slugs (A.K.A. friendly IDs, vanity URLs) to identify records instead of numerical IDs […].

Lend-to-Friend assigns users an ID by incrementing a simple counter and user’s ID can be found in URLs and in HTML source. As a result, if my application were released into production it would leak information such as my total number of users and my application’s user growth rate to competitors. Perhaps exposing user number and growth-rate isn’t a problem that matters for my application, but if I’m hadn’t been aware that I had a leak in the first place, I can’t make an informed decisions about whether or not it is worth it to me to fix.

Final Thoughts

The process of trying to identify data leaks and security vulnerabilities in my code didn’t turn me into an overnight security expert but it did give me a chance to wrestle with just how difficult information security can be and to hopefully gain a little exposure into the process of trying to identify potential vulnerabilities before they become a problem.