Recursion

My first taste of recursion in the realm of computer science was when I learned that GNU stood for “GNU’s Not Unix”. “That’s cute”, I thought to myself, “I guess it must be a programmer thing”. As I’ve delved deeper and deeper into programming, recursion as a concept has gone from novelty to necessity. Recursion can be a bit heady and discussing it thoroughly treads on the edges of some complex issues in computer science; I’ll do my best in this post to share my understanding of these issues but be warned that I am most certainly still working them out for myself.

Recursion? Huh?

Recursion sounds kind of intense and frankly, in practice it can look pretty intense too, at least at first. However the concept of recursion isn’t really all that challenging to grasp. Recursion, in lay terms, is really just a definition for something which refers to itself.

Have I lost you? Probably I have. Let’s try an real-world example. As an amateur bread baker I’m a big fan of the example used in the Wikipedia article for recursion: A sourdough recipe. Many recipes for sourdough include the key ingredient of “sourdough”. For those readers that aren’t aware, Sourdough is basically just a culture of various yeasts and bacteria. An addition of left-over sourdough from a previous batch to a new batch introduces the microbes to the dough and, given the right conditions, the microbes will reproduce and create a whole new batch of sourdough.

Most baker’s who work with sourdough regularly know to keep a bit of sourdough (known as “starter”) on hand for the next batch of dough. Therefore, it usually makes perfect sense to have the instructions for making a new batch of sourdough reference the requisite sourdough. For those that have never made sourdough before, however, this recursive recipe style begs the question: Where does the sourdough come from?

For effective use of recursion in computer science, this question is pretty critical. While a human being is likely to ask a friend or run a web search for “how to get started with sourdough”, a computer would simply try to spiral down the rabbit hole forever:

Make Sourdough > Add Sourdough >

Make Sourdough > Add Sourdough >

Make Sourdough > Add Sourdough >

...

Recursion in Computer Science

In mathematics / computer science, a practical implementation of recursion requires two things:

- A “base case” which is one or more conditions for termination that operate independently of recursion

- A set of rules that reduce any other case toward the base case.

In the case of our sourdough example, the reducing rules are akin to the instruction to add your previous sourdough while a hypothetical base case might be something like a statement that reads “if you haven’t made sourdough before, go to page 22 for sourdough starter”. One can think of this recipe as a recursive function which instructs one to trace the full set of steps they performed in order to create their loaf, including all the previous batches. With the help of this base case, the process now looks something like this:

Make 3rd Sourdough > Add Sourdough >

Make 2nd Sourdough > Add Sourdough >

Make 1st Sourdough > Add Newly Made Starter >

Starter > [INSTRUCTIONS FOR MAKING STARTER]

Make 1st Sourdough < Add Newly Made Starter <

Make 2nd Sourdough < Add Sourdough <

Make 3rd Sourdough < Add Sourdough <

That’s pretty cool and all but what exactly is the point? A common practical example of a recursive algorithm is factorials. In Ruby, a recursive factorial algorithm might look like so:

def fact(n)

return 1 if n <= 1

n * fact(n - 1)

end

Given a positive integer n, this function would recursively call itself on the next lowest integer until it reduced itself to 0. The execution of this function would look something like this:

fact(4)

4 * fact(3)

4 * ( 3 * fact(2) )

4 * ( 3 * ( 2 * fact(1) ) )

4 * ( 3 * ( 2 * 1 ) )

4 * ( 3 * 2 )

4 * 6

=> 24

Recursion v. Iteration

When I first saw the application of recursion in a program my mind was entirely blown. I was asked to write a function that returned the nth number in the Fibonacci sequence where n is a positive integer. The Fibonacci sequence is defined as a sequence of integers in which each number after the first two are the sum of the proceeding two numbers. The code I wrote was a somewhat more verbose version of this:

def fibonacci(n)

new, current = 1, 0

n.times do

new, current = new+current, new

end

return current

end

As it turns out, for any given iterative (ie. a series of steps building upon the one before like a loop) solution to a problem there is also a recursive solution and vice versa. After completing my solution, someone showed me the following recursive solution to the same problem:

def fibonacci(n)

return n if n < 2

fibonacci(n-1) + fibonacci(n-2)

end

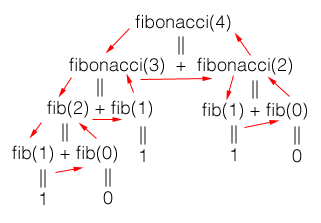

This code is bit different from the previous examples of recursion because it runs down two trees of recursion. To get an idea of how this code would function when executed check out this diagram:

Courtest of Matthew Adams on Stack Overflow

Courtest of Matthew Adams on Stack Overflow

As you can see, each side of the tree reduces down to either one or zero and then the results filter back up the tree until they reach the final simple addition problem. Once this sinks in it is pretty staggering. When I finally got a handle on what was going on my brain immediatly lept to the conclusion that because recursion was complex and new it was certainly the most advanced and preferred method for any and all programming work of real substance.

As I’ve previously written about however, it can be incredibly tempting to believe that code which is difficult or uncomfortable to understand is somehow therefore superior. This is not always the case and in this particular instance it is decidely not. Recursion has many stellar applications and advantages over iterative approaches. This does not appear to me to be one of those ocassions. While the fibonacci sequence makes a wonderful example for teaching recursive algorithms the basic algorithm above is actually a pretty poor solution to the problem. The bigO, or theoretical runtime efficiency, of this alogrithm is O(n2). That means that as the value of the input n increases, the algorithm will take an exponentially longer time to complete. My initial iterative solution, on the other hand, has an efficiency of O(n). Ie. the time it takes to solve the problem should increase at a linear rate as the value of n grows.

Strategies such as memoization can improve the runtime efficiency of a recursive solution at the cost of some increased memory utilization. Memoization in this case would avoid duplicative work by caching the calls that have already resolved and checking that cache before calling them again. Even if the space trade-off of memoization were deemed acceptable, the recursive solution has another significant downside: Stack overflow.

Stack Overflow

A given program typically utilizes two types of memory: Stack and heap. Without digging too deep into this area let’s consider a program with a single stack and a heap. The amount of memory set aside for the stack typically remains fixed in size while the heap size can change dynamically if needed. When a recursive function call is made, each of these calls takes up it’s own space in the stack. This is not a trait shared by recursive algorithms. The deeper and wider the recursion, the more nested calls are made and the more data is filled up in the stack. At some point the stack will run out of space leading to a “stack overflow”. The size of the stack and nearly every other variable in question will vary depending on the particular language in use and/or the quirks of the particular environment in which the program is run. For the the recursive Ruby code above that means at a comparatively small value of n (I’ve seen 7500 as one estimate) the code will return with

SystemStackError: stack level too deep

The iteration solution, however, can handle far larger values of n.

Conclusion

Recursion was a challenging subject to start to get my head around and there is a mountain of information still to digest about the comparative advantages and disadvantages of recursion and iteration in various contexts. As powerful as recursion can be, I’m glad to now have a better sense of where recursion’s pitfalls lie and how to better spot them.