What Makes "Good" Code?

As a relative newcomer to software development I have tried, wherever possible, to practice good programming habits. I’ve picked these habits up from resources along the way, and sniffed out some through experience and instinct. As I write my code I try to pay attention to conventions on style, approach, and organization. I look at style guides and emulate the best practices I can find and I do my best to constantly cultivate and nurture that little voice in the back of my head that says things like “this feels wrong, there must be a better way to do this” or “you may not care about it right now but when you come back to this in a few days you’re going to really wish you had…”.

The more I work with software source code, the more I am beginning to realize that “good” code isn’t as clear cut as I might have imagined. It seems like a tangled rat’s nest made up of equal parts good habits, good instincts, and idiosyncratic preferences. I’m going to use this blog post as an opportunity to share what I’ve learned so far in my journey about what makes good code “good” and the sense that I have tried to make of the subject.

Good Code Works

Although there is a decidedly subjective element to the notion of “good code” there is one characteristic that seems to be accepted nearly universally as a requirement for quality software: It must work correctly. Yup, you heard it right, the very first rule of writing truly great software is to make sure that the software is functionally suitable for its intended use. That means it must be delivered on time and is able to be deployed for real-world use. The fundamental goal of software is for it to be used to serve an actual purpose by real people in the real world.

Everything Else

Aside from working and being delivered on time, different people place different emphasis on different characteristics of code when deciding its merit. Aside from functional adequacy there are really only a handful of broad virtues of software code that I have identified:

- Ease of Testing

- Ease of Review

- Ease of Modification

- Optimization/Efficiency

Each of these virtues is aimed at ensuring that our code can be improved upon and put to use in production in the minimal amount of time, with the minimal amount of frustration and with the minimal potential for bugs. In other words, to steal a line from Joe Ferris, “[c]ode is good when it works and we can work with it.”

Optimization/Efficiency

We should forget about small efficiencies, say about 97% of the time: premature optimization is the root of all evil. Yet we should not pass up our opportunities in that critical 3%

— Donald Knuth (esteemed computer scientist and founder of Tex)

When I first started to dip my toe into the world of software development I believed that truly excellent code was synonymous with the kind of highly optimized rarefied code that one really needs to know one’s stuff in order to comprehend much less to write on one’s own. While I still believe that good programmers should avoid introducing needless inefficiencies in to their programs I no longer feel that the efficiency and conceptual complexity of code is the primary indicator of its overall quality. In fact, I now realize that when efficiency comes at the cost of increased complexity and decreased readability it can often result in a net decrease to code quality.

Ease of Review

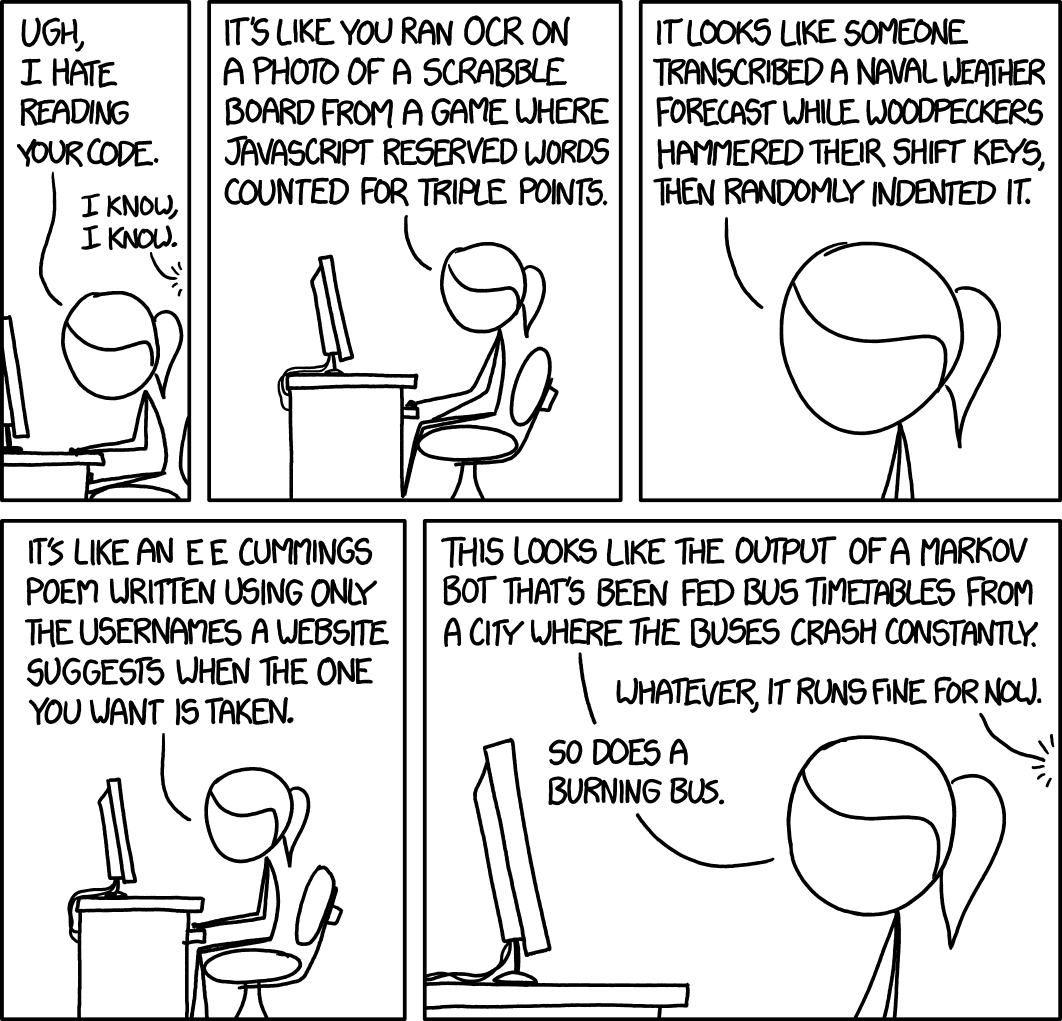

It seems that a lot of developers have the sneaking suspicion that this is how anyone who sees their code will react. Comic courtesy of XKCD

It seems that a lot of developers have the sneaking suspicion that this is how anyone who sees their code will react. Comic courtesy of XKCD

Chances are that someone, at some point in the future, is going to need to review your code without the benefit of having you walk them through it step by step. Maybe that person is your boss or coworker, or maybe that person is your future self. Readablity of code is therefore critical. Readable code should be well commented and include descriptive naming of variables and functions. Readable code should also be well-organized and well-formatted. Although there is a degree of subjectivity in one’s choice of style or convention, remaining consistent within one’s code can be a major factor in ensuring that code is easy to read and to understand. This is where conforming to well-defined style guides and using common patterns/conventions can be incredibly valuable down the road.

Testing/Testablity

Test-driven development is a software development methodology in which automated tests are written before coding any new feature. Test-driven development can be a powerful strategy for protecting against inadvertent defects in software and can significantly decrease the friction a new developer experiences when beginning work on an unfamiliar codebase.

I am only just beginning to learn about writing tests and testable code and although Miško Hevery’s Guide to Writing Testable Code is a bit above my head at the moment, I look forward to learning more as I continue to grow as a developer.

I am, however, already familiar with the benefits of a well-crafted test suite (and unfortunately the frustration that often comes with brittle tests). Well tested code allows me to understand the impact of the changes I make in a codebase and allows me to narrow my focus to one clearly stated digestible problem at a time.

Ease of Editing

Unless you are a perfect developer working in a perfect world, there is a very high chance that at some point someone will need to make changes to your code in order to fix a defect or extend its functionality. In many respects, both testing and readability factor heavily into whether or not a piece of software can be easily modified. Software which is easy to modify must be understandable and it can be a great asset if tests are already in place to ensure that modifications can be made with some degree of confidence that they have not introduced unanticipated defects into the code. This is also where the downsides of highly complex code can really start to show itself: complex code is hard to write but it can often be even harder to edit!

There are a number of practices that can really increase code’s suitability for editing. For example, the DRY principle (“Don’t Repeat Yourself”) which provides that developers should not write code to perform the same function two different times, helps to make sure that any future modification to that functionality will not introduce inconsistency between different parts of the program. Another common set of principles for object oriented programming is SOLID. SOLID is a collection of five principles which are intended to make code easier to maintain and extend:

- S - Single-Responsiblity

- O - Open-Closed

- L - Liskov Substitution

- I - Interface Segregation

- D - Dependency Inversion

Following these sorts of practices may not always feel convenient in the moment but their value often demonstrates itself over time when you or other developers are asked to return to code at a later date in order to make modifications.

Bringing it All Together

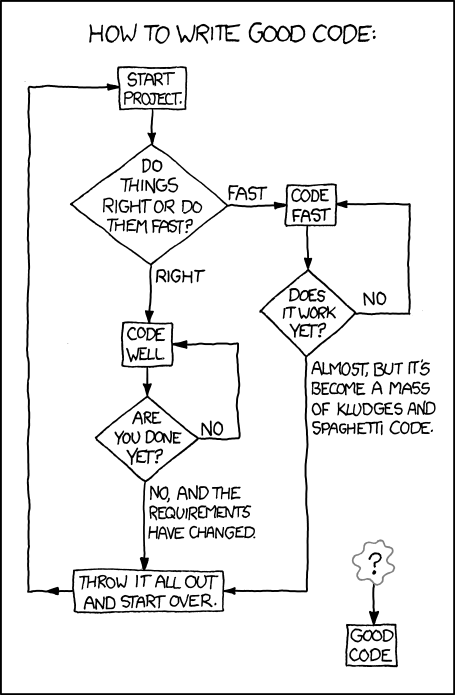

Do it right or do it fast?. Comic courtesy of XKCD

Do it right or do it fast?. Comic courtesy of XKCD

Writing great code isn’t necessarily about writing complex code. It is often, more than anything, about cultivating good habits and ensuring that we think not only about what works for us in the moment but that we invest in the softer elements of our code to ensure that it will be usable by ourselves and others in the future. After a good deal of thinking on this subject, the maxim “make it work, make it right, make it fast” is finally starting to sink in.

As I continue to develop as a programmer I’m going to focus on getting better at seeing where I can create the most impact with the least effort in my code. The goal is that eventually writing “good” code will be more automatic than deliberate.